- Ruby Hall Clinic, near Wanowrie, Pune, Maharashtra

- Mon - Fri: 9:00 am - 4:00 pm

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectet eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore e rem ipsum dolor sit amet. sum dolor sit amet, consectet eiusmod.

Visiting Hours

| Mon - Fri: | 8:00 am - 8:00 pm |

| Saturday: | 9:00 am - 6:00 pm |

| Sunday: | 9:00 am - 6:00 pm |

Gallery Posts

The Unusual Suspect.

This is a case that I will probably remember throughout my practice. It is special because it is actually a theory coming to reality. It is the case of a 39-year-old female, overweight, who was being treated by her family physician in view of hypertension. Hypertension at such a young age is unusual, and the patient was already on 3 medications to control her blood pressure. The patient reported having fatigue and chest pain on exertion for a very long time (approximately 2 years). She had visited multiple hospitals in the past 2 years but was sent back home, and her symptoms were trivialized. The patient started limiting her activity and was confined most of the time to her house, apart from going to her office for work. The patient is an avid foodie, so she naturally started gaining weight (more calories being credited and no debit in activities, so her bank calorie balance (body weight) was growing!)

The family physician to whom I was recently introduced decided that the patient should see me in view of her long-term symptoms. The patient and her husband came to my OPD, and we had a discussion about her case. In our discussion, I could deduce that although her symptoms were cardiac, they were quite non-specific. We decided to stratify this patient by doing some basic cardiac tests and blood work. In the patient interview, there was a red flag: the patient’s father had a heart attack at 33 years of age, and his paternal grandfather had died in his early forties of a cardiac problem.

During the evaluation, patients’ ECG and 2D echo turned out to be normal (as is the case in most individuals until and unless they have already had a heart attack, then these tests come out to be abnormal). I asked the patient to walk on a treadmill with an ECG hooked up, and to everyone’s surprise, she couldn’t walk for even 2 minutes. My team and I thought of 2 differentials at this stage, the first being de-conditioning, a situation where the body is not used to exertion at all, so a person cannot walk and gets fatigued in 2 minutes, or the most dangerous of all, a blockage in the coronary vessels, the blood vessels that supply the heart.

I counseled the patient and her husband about the need for further investigations, and they were cooperative enough to agree to a CT (coronary angiogram), a simple test that delineates the blood vessels and gives an idea of blockages. The patient visited the facility, and the investigation was done the next day. I got a call from the Radiology Department immediately, as they were in disbelief seeing the images—a young 39-year-old lady with tight blockages in all three blood vessels supplying the heart!

I contacted the husband to come down to the OPD, as it had now become an emergency. Meanwhile, her blood work came up, which showed her LDL cholesterol to be 297 mg/dl (the ideal upper limit is 90). Her condition was akin to a time bomb; it could blow up any minute. As a routine OPD patient, she had become an urgent case!

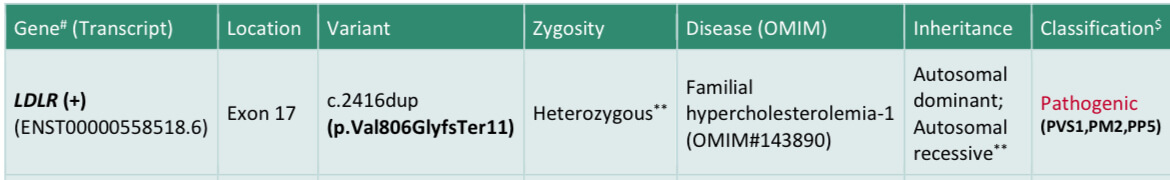

The patient and her husband agreed to an admission, and her insurance company was contacted. Unfortunately, the day of the procedure was a national holiday, so the insurance company was short-staffed, and the approval took an unusually long time. Finally, the patient was up in the cath lab, and the picture of her angiogram was worse than what we anticipated from the CT angiogram! She had blockages in the left main artery along with all the 3 blood vessels. Post-angiogram, I spoke with the relatives and showed them the images. They had 2 options: bypass surgery or a very complex angioplasty. The patient was on the table, her immediate kin was to take the call, and to my surprise, they rejected the idea of bypass surgery at such a young age and trusted me with her life to do an angioplasty!

Pre angioplasty

Left-main bifurcation angioplasty with a critical right-sided lesion is considered the most challenging case for an interventional cardiologist, and I was put up to the task by the family members. These cases are usually turned down by even one of the most experienced cardiologists, as a procedural death brings in a bad reputation. I took up the challenge, and God was kind enough to be on my and my patient’s sides. The procedure went smoothly, and my cath lab team could deploy 3 stents, clearing all the blockages that the patient had! It took us almost two and a half hours to do this complicated procedure. The procedure was OCT-guided, a special tool in the armamentarium of a cardiologist that images the blood vessels from the inside and is regarded as an essential tool in the cath lab, although it has limited availability.

Post angioplasty

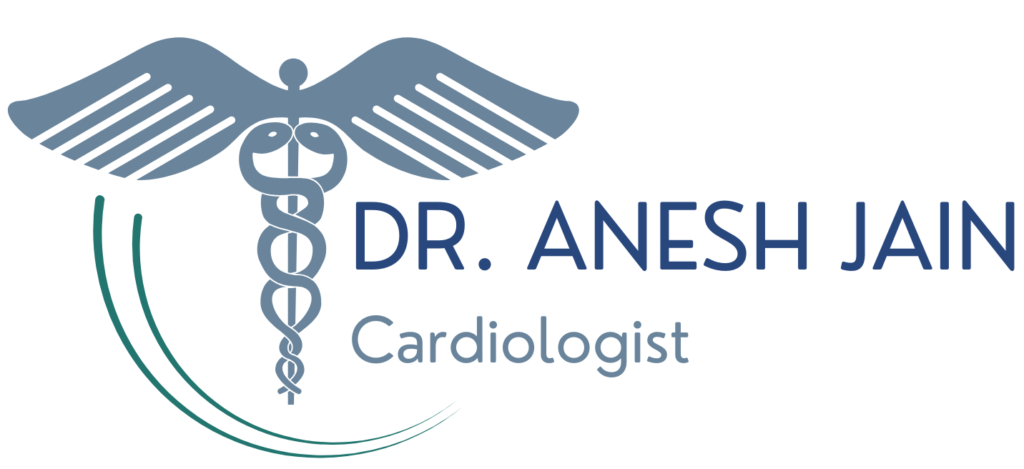

The patient had an uneventful recovery post-procedure and was discharged with oral medications. In view of a strong family history, I counseled them to get a genetic test done, which the patient agreed to. The patient was also started on an injectable medication to reduce her LDL cholesterol so that future recurrences could be prevented. The patient is now following up in the OPD, able to walk around without any symptoms, and her genetic analysis indeed came out to be positive—she has a genetic mutation in the LDLR gene, which makes her liver incapable of handling cholesterol! This gene was responsible for disease and death in 3 generations of her family. Although the genetic code of the patient cannot be changed now, it is possible to treat the result of this mutation with an equally potent injectable medication, Inclisiran!

Lessons learned from this case were that it is important not to trivialize any symptoms by the patient, an in-depth discussion with the doctor is still relevant today, and cooperation from the patient’s side is important to get the optimum treatment at the right time! The patient was indeed an unusual suspect for such an aggressive disease.

Regards,

Interventional Cardiologist

Ruby Hall Clinic